The late Lee Kuan Yew was without doubt an

extraordinary person. Say what you like about the late Mr. Lee but on the whole,

he did good for Singapore. Sure, I have my grouses about Singapore and how life

has become expensive. However, as one Dutchman said to me “Where else is there.”

If you think about it objectively, Lee Kuan Yew got most things right and I

will never tire of saying this but Singapore is pretty much what any city or

country should be – clean, green and rich.

However, while Mr. Lee was undoubtedly an extraordinary

leader, he developed what one could call a glaring flaw. In his later years as

a consultant to nations, he developed a philosophical aversion to natural law –

namely an aversion to the laws of natural selection. He seemed to genuinely

believe that the system he created, which was all about the perpetual rule of

an “intelligentsia” concentrated around his family (both his actual family and

political party) was the best possible system for Singapore and would last in

perpetuity.

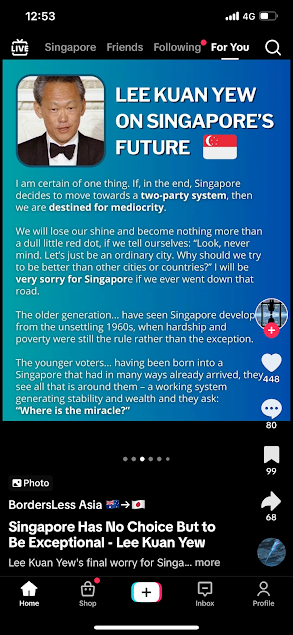

The man who forged a nation where citizens pledged to “build

a democratic society, based on justice and equality” ended up arguing that

Singapore would be undone by a “two-party” system and while Mr. Lee had the

wisdom to know when to curb himself (let’s remember he voluntarily stepped

aside and made his successors remember to let him come to them), this wasn’t necessarily

the case with the people after him. Whilst Singapore’s political system seems

to continue to deliver the proverbial goodies, one cannot help but feel that

there is a genuine belief in the elites that they have received the “mandate of

heaven” to be where they are. I mean, which other “free-market” capitalist society

actually has business leaders saying “the market is too small for competition.”

So, was Mr. Lee, right? Is an iron grip on power

better for the economy than letting people do what they want? Sitting in

Singapore, which seems relatively stable (no Trump and no Brexit) compared to

pretty much most of the world, the answer might be yes.

However, around November of last year, I attended a

talk by His Excellency, Mr. Ignacio Concha, the Chilean Ambassador. This was a talk

about investment opportunities in Chile, which is the most advanced economy in

South America.

Chile's “success story” once made it comparable to an Asian Tiger economy rather than a Latin one. More importantly, Chile was once run by a strong man, called Augusto Pinochet, who along with murdering millions, actually stabilized the economy and set Chile onto the path of growth and development.

One might argue that Chile under Pinochet was a

classic example of the benefits of strong man rule. However, the Ambassador

made the point that the real explosion the Chile's growth came in the decade

after the return to democracy (1990). If you were to look at World Bank

statistics, you would realise that the Ambassador is right:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=CL

If you look at the statistics closely, Chile’s real explosion

didn’t happen in 1990 with when Pinochet stepped aside but in 2000 when he was

arrested in the UK on the orders of the Spanish Magistrate Baltasar Garcon.

This marked the beginning of the end of his influence on the country.

So, while there is a case to say that Pinochet, for

all his faults, did stabilize the Chilean Economy, there is a case to say that his

influence held the country back and the country only started exploding into

wealth and advancement when his influence over the country ended.

There’s a similar example closer to home. In South East

Asia, there is Indonesia, which is by far and away the economy that counts on

the global stage. For 30-years, Indonesia was run by a strong man. Like

Pinochet in Chile, Suharto had millions killed. However, he was a stable force

in Indonesia and the ASAEAN region. Coming from Singapore, where there are

memories of “Konfrontasi” under his predecessor, Sukarno, Suharto was a vast improvement.

He kept Indonesia stable and focused on itself rather than on us, which allowed

us to grow.

When Suharto fell, it seemed that things were a little

bit messier. However, if you look at growth figures, Indonesia has done exceedingly

well and being the world’s third largest democracy has been good for Indonesia’s

entrepreneurs. The years under Jokowi, Indonesia’s first entrepreneur president,

have been particularly good for growth:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=ID

On the African continent, there’s Nigeria. Like

Indonesia in South East Asia, Nigeria is the giant in its neighborhood. For the

better part of its Independence, Nigeria was run by its generals. There were

periods of vast growth, which were then followed by economic collapse. Nigeria

was effectively driven by oil exports. Then, in 1999, the last and worst of its

military dictators died. Nigeria returned to civilian rule and growth has been

steady. While Nigeria has by no means escaped poverty, its been remarkably

steady since 2000.

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=N

So, if you look at the examples of Chile, Indonesia

and Nigeria, there is a case to be made for democracy being good for growth.

Yes, rule by strong men can be necessary to bring a sense of stability.

However, that’s only good up to a certain point. A lot of the benevolent effects

of strong man rule depends on the strong man himself. In Singapore, we’re lucky

that the “strong man” was Mr. Lee who got things right and saw to it that his

immediate successors remained honest. However, there’s no guarantee that the

next few leaders will remain honest or get too used to the perks of power.

Nigeria’s plethora of military strong men turned what

should be an exceedingly wealthy place into a basket case. Suharto was a force

for stability but when things collapsed in 1997, he was exposed as being more

interested in hanging onto power to protect family wealth than running the

country.

Democracy and competition for power are actually good.

When you let people get on with it within a certain framework, you actually

create prosperity. It may look messy and ride may be rough, but in the end, letting

people get on with it and making them have a stake in the country is actually

good for everyone

No comments

Post a Comment